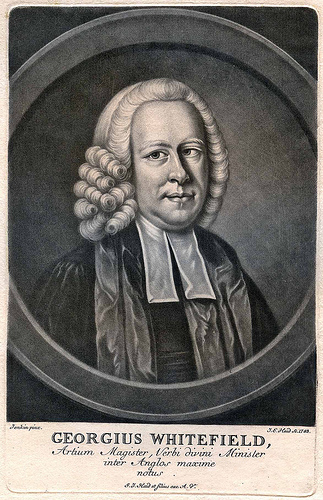

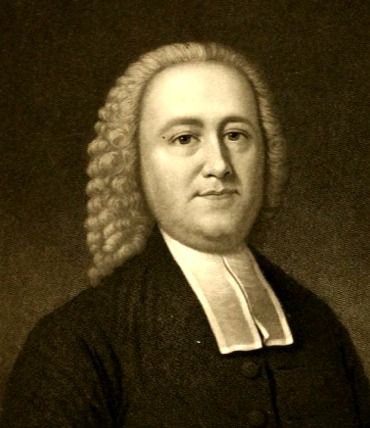

Revivalism crossed the Atlantic Ocean to the American colonies through the likes of George Whitefield, who came to Boston in 1740. His arrival was welcomed by the likes of Thomas Foxcroft, who was concerned with the cold rationalism of the day and was pleased with the Whitefield’s counter-message. Regarding Whitefield, Foxcroft said in a sermon, “We have in a fresh Instance seen this Pauline Spirit and Doctrine remarkably exemplify’d among us. We have seen a Preacher of Righteousness, fervent in Spirit, teaching diligently the Things of the Lord.”

Whitefield’s arrival in itself was not without much fanfare. In 1739, newspapers in New England carried stories of the crowds that would gather in England to hear him, and about his novel preaching style. Whitefield was known to give sermons outside, in fields and on streets, on a tree stump or on even while on a horse. New Englanders were eagerly awaiting the arrival of this pious man so that by the time he arrived in Newport, he was received “as the apostle St. Paul was received by the churches of Galatia…”.

What Whitefield discovered in the New World was a religious condition somewhat better than in England, but still lacking. Ministers did not have knowledge of Christ.

Students at Yale and Harvard were reading from the likes of John Tillotson and Samuel Clarke, authors who were concerned more with philosophical and moral religion rather than “essential Christian doctrine”. Although the faculty at these two schools eventually opposed the revivalism sweeping through New England, the movement would eventually garner enough support to establish a school all its own in 1741, which they called Princeton.

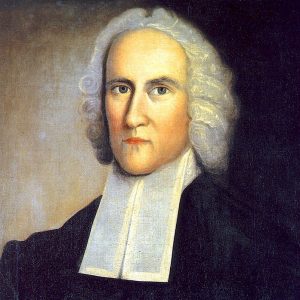

Around the same time in America the Great Awakening developed as a theology of “total dependence” on the transformative emanations of the Holy Spirit under Jonathan Edwards. Edwards argued that Lockean “sense impressions” of most importance were those which saw and felt God, since they affected human growth. Confronting his congregation, he pitted two images – images of “Sinners in the hands of an angry God” against those of “the divine and supernatural light”. The result of such sermons during the 1730s brought society in the Connecticut Valley to remarkable conversion and interior reflection. This revivalist sentiment spread throughout New England in different degrees throughout the decade, with another resurgence or zeal occurring in 1742-1743.

Throughout the Great Awakening, a number of things started to happen within the minds of the colonists. The rural commoners, interested in social equality, began to take hold and migrated to the New Light camp. They began to question the authority of church leaders and rebel against their own church ministers. The New Lights were taught a kind of anti-intellectualism. The New Lights – or the new ministry of evangelicals – were more apt to engage in enthusiastic groans during worship than their traditionally silent Puritan counterparts. Above all the effect of revivalism was a change in power from the hands of the clergy into the hands of the congregation.

Revivalism was not without opposition during the Awakening. After the infamous slave conspiracy of 1741, it was Whitefield who was blamed with encouraging the incident because of his desire to see the negroes converted. Whitefield was accused of having done a number of things to stir them up, and he was even accused of being in league with the Catholics. Revivalism was also opposed by those centered on theology and its relation to rationalism – also known as the “Old Lights”.

The Great Awakening had its zenith in the middle and upper colonies under Whitefield but eventually faltered. Part of this was due to Whitefield’s successor, Gilbert Tennent. Although Tennent possessed some of the same passion as Whitefield, he lacked the polish of his mentor. Tennent’s abusive personality tended to alienate some from the revivalist movement, particularly when he would lampoon his opponents with various epithets.

The movement was also discredited by the excessive emotions that increased as it continued through the years. Edwards observed the increase in strength of emotions exhibited by believers between 1735 and the 1740s. One of the great revivalist figures in emotional excess was preacher James Davenport, who would travel around New England and examine local pastors on their knowledge. When pastors would refuse Davenport’s request, he would denounce them and label them “unconverted”. Meanwhile, he would preach in town to his admirers, who at times would report visions and trances.

Further reading

Jonathan Edwards: A Life, by George M. Mardsen

Forgotten Founding Father: The Heroic Legacy of George Whitefield, by Stephen Mansfield